Photo by Anita Morse

By Curlee Raven Holton, 1992

Until last year, Todd Ayoung’s paintings were lush and colorful, a fantastic garden growing pink and blue plants and severed limbs, watched over by half faces, trodden by the bullet gray feet of Christ. This year, as part of the Whitney Independent program, his work is black and white. Card catalogues from libraries obscure engravings of American slave life, their dry, descriptive titles clarifying what is hidden. Todd Ayoung met Curlee Raven Holton when they were both fellows on an NEA Fellowship, and their ensuing collaboration led them to explore common ideas about art and disenfranchisement.

Curlee Raven Holton Todd, when we first met each other, you were showing me around New York City. Something you told me then, was that you carried an imaginary community with you as you traveled around the world, and that that community has traveled with you through your art work.

Todd Ayoung I originally came up with that idea from reading Edward Said’s book, Orientalism, where he describes imaginary geography. What that meant to me was that, as opposed to the West trying to impose a preconceived image of what the Orient is, or to construct the Orient … we have reached this imaginary state that the West has constructed, we’re living, as people of color, in an imaginary construction. And this “imaginary” community is real for the white communities … I use white community only in terms of an ideology; whiteness as an ideological state of mind, not a biological one. That’s a very important differentiation when you’re talking about white supremacy. The imaginary community is something that I feel I am reconstructing, I’m turning it around.

CRH When we jump into your work feet first—and your images are often just legs or just an arm—your work speaks of this imaginary community, touching and being a part of it. How has that philosophy evolved over the years?

TA I originally started to invent a landscape. I went to the traditional landscape: the sky, the atmosphere, the earth and a sense of gravity, being part of the whole system of the horizon. What I wanted to do was to invent this imaginary community, a kind of ecological space where I could live … symbolically.

CRH I noticed what seems to be foliage, a jungle environment, but not in tropical colors. It makes me think of being back in the Garden of Eden.

TA This imaginary geography is a kind of idealism, a Utopia. Trying to develop that is very important as a space of empowerment, but there’re a lot of limits to that vision because it has a nostalgia …

CRH … a romanticism to it.

TA For a place that does not exist.

CRH Are you creating a place for yourself or a place for the viewer?

TA In the first series, the “Race” paintings, I tried to construct a geography out of my own head. And it was for me. I was trying to stake out territory before I could affirm my subject.

CRH I found, as an African-American, that you were speaking to many issues that I was confronting: the issue of other, difference, the relationship to the world around you, and the way of insulating yourself with this imaginary world that you’re creating. Can you speak about the exhibit you had in Europe recently?

TA I had a show in Austria called A Tourist is an Ugly Being. The title comes from a Jamaica Kincaid book called A Small Place. She gives not only a description of an individual, but also created an ontological state. Tourism has now reached a historical point, where it is an ideology that has nothing to do with trying to find out about the other, how the other lives, as much as trying to affirm a dominant position over the other. So this work brings out what it means to be an intruder even in the most economic sense of just relaxing and getting some sun, it’s a major disruption, from colonialism to tourism. The pieces that I did recently, New World Plantation, had to do with the foreign policies of the United States, that try to bring back a sort of plantation system within dependent economies.

CRH You work with what are often called “marginalized” people, such as African-Americans and people of color. You do a lot of work with progressive organizations, like Repro-History, which attempts to discover and restore historical facts that have been dispossessed.

TA Or are absent.

CRH … or overlooked altogether. This is the repossession of art history. Is your connection to that also a desire to repossess Todd’s world? To go back and repossess a history that has a positive relationship to the rest of the world. Because being the “other” has negative aspects and feelings to it. I see this also in my own work. Recently, we worked on a large collaborative piece: a monoprint you titled, Coal Traces.

TA I like to collaborate because it helps me to get outside of myself. A lot of my work has to do with colonialism, or neocolonialism, and racism. In your work, you have articulated through a language you are constantly developing in your printmaking and your painting … you have a grasp of something that I’m still trying to get a hold of. Maybe your community is stronger. So I’m trying to hook into people’s communities. In a way, I’m a parasite. But I’m being a parasite to construct my community, which may be imaginary, which hopefully will become real. And the more I hook on to other people’s communities, communities of Asians and African-Americans, for my own sake and understanding, my community seems to have grown into a hybrid state.

CRH Let’s talk about the Race and Culture show. How do you fit into a context of shows that are defined as race and culture exhibits?

TA In multicultural shows, I always have a kind of caution, especially if it has to do with a person who’s not categorized as a minority, it makes me question it. Especially now, because it seems to be fairly trendy. There are a lot of exhibitions right now having to do with issues of race and culture. It becomes a commodity for a short period of time and there’s a turnover constantly. And so it relieves the responsibility, and puts a few stars into position, that they can use, and say, “Look, he or she (most likely it’s a he) has been showing and getting lots of money.” There’s also a codification of racial issues in this culture, a circulation of values, meaning that things go on a monthly basis, like Black History Month. So I’m suspicious, even though the gallery is made up of women who are concerned with these issues because they’re concerned with women’s issues and the larger context. For example, the presentation of the exhibit, like the announcement, that just divides up the space between black and white and presents race in culture, but does not name the participants, the subjects do not have any personality. By showing who these people are, you have a development of their work, of their personalities. Also you know that they are not in this just because it is hot at the moment, that this is something they are continuously doing. This seems symptomatic of the gallery situation, even though I know good intentions are involved, there is a certain oversight.

CRH Often artists of color are not only speaking of race and culture, but are speaking from a perspective of being a victim of such categories as well. If one’s work is only seen in that context, this construction is one of restriction, raising the question, is the phone ringing for an artist or for a black artist? As an African-American artist you often have to choose between this type of exposure or no exposure at all. How does the Race and Culture show contextualize your work and, most importantly, how does this contextualize you? You’re often included in African-American exhibitions of this kind, but you are not African-American.

TA It is true I am not a black artist, but I consider myself a black artist in the British context which is a different thing, because I come from a British colony. For Britain, if you are not white, you are black, so there’s a clear distinction and I like that, there’s a polarity. An opposition and a unity involved with deciding.

But the other aspect is the African diaspora, which is part of the Caribbean, where I grew up, my culture and my background. So most of my work is from an African point of view, even though I’m part Chinese and Indian. That plays a big part in my interest to gain a respect and a community among the black artists.

As an African-American within American culture, your position and community are more defined, while mine is defined by my being an immigrant, being of that artificial construction of the Caribbean. I’m curious about your audience.

CRH I evolved as an artist with an exclusively black audience. As well as communicating to this audience, I felt my role was to somehow serve that community with my creative talents. So early on, my work was celebrating what it meant to be an African-American. But as time went on, I began to realize there were other meanings, that I had to lift it up somehow, connect and relate to other audiences.

TA Did your community become larger, through your collaboration with me, as it relates to the diaspora?

CRH Our common experience was intriguing, this relationship to the Anglo-European world that is so consistent among people of color. There’s a bond, not always cultural, as in foods and language, but clearly, we are not white and not being white in this world is significant. That helped move my work to a larger context. Knowing that I am but a finger on the hand of this experience has made my work more confrontational. I’m returning to African icons or symbols, relating a contemporary cultural article like an afro-pick or a hot comb and placing it on the pedestal of Art. So what I do is take things associated with the African-American cultural experience and highlight them, re-contextualize them. That I think is the power of an artist. To speak the unspoken.

When it comes to white audiences, my effort is to speak of my experience as a person of color in our society and refer to the universal aspects of exclusion. I attempt to reveal my experience as an African-American as a metaphor for a much larger meaning.

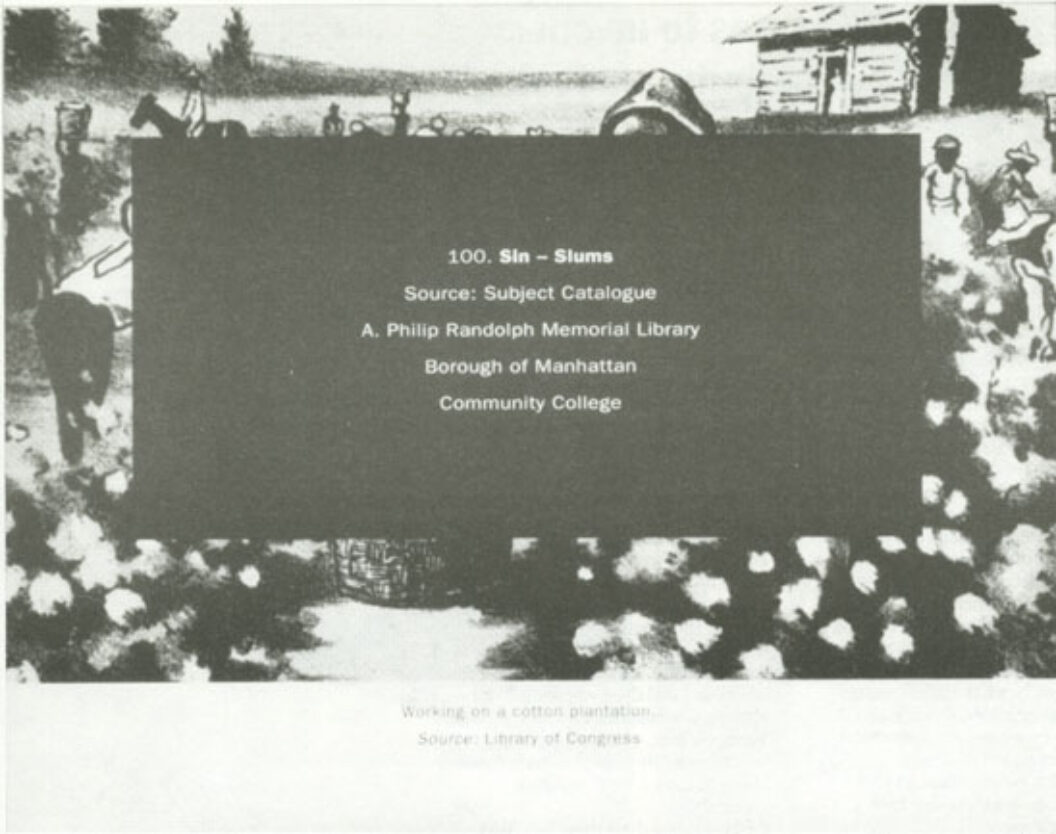

Todd Ayoung, from the New World Plantation series, 1991. Installation.

TA Not only how we are subjects of history but how we are subjugated by history.

CRH That’s why I think the works of African-American artists display such power and potency, part of that potency comes out of the pressure of that crucible of racism and exclusion. The work of David Hammons and Adrian Piper are two examples of this. Also, exclusion forges a different language, a different relationship to existence, different realities and, consequently, different methods of perception.

TA You have to open up and realize that you are a part of a human culture. That we have to go beyond racialization, yet retain our difference.

CRH Todd, your work seems to be postmodern; you utilize modern techniques to refer to historical issues of exploitation and images of slavery, and bring these issues into the modern discourse by your choices of subject and technique.

TA The piece that you are referring to speaks to a continuing language within the system. Even if the objective is to present slavery in an un-hypocritical way, there is a continuation in the language and the attitudes. In this case, in the way things are catalogued in our libraries, like “natural history-negroes,” that illustrate the whole ideology of the system. You didn’t ask me this question, but since I am not African-American, you could ask me how I could get lost in that process, because there are no images of me, except for a quotation that says, “When I was 14, living in LA, I tried to erase the color from my junior high school photo because I thought it was too dark.” Then I bring it up to the present situation: “Is the bombing of Iraq another form of erasure?”

CRH Does being marginalized or denied access offer you a new community?

TA The weight falls in different places, there’s a kind of movement. To some extent, I am gaining a community. I’m also engaging in a larger conversation, one of diverse views. Among the artists I am meeting, I find there are some like Leela Ramotar, Ayisha Abraham, Fred Wilson, Yong Soon Min, who are very important for my dialogue, my contexualization, my ability to have a “real” imaginary community.

CRH Do you think there is a Black aesthetic, an other aesthetic? Or is it placed on the work?

TA Up to date, we are the victims of our own aesthetics. But we can make use of what we have: reverse it, expand it, and legitimize it to where it becomes the master of that history. Not that we want to play a master-slave game, but we have to understand what takes place within that conversation as well as the dialectics involved in re-positioning and re-contextualizing ourselves. There is a big loss in creating a community as well being racialized, being called a person of color and having shows around it, and always worrying that tomorrow people won’t be interested in this subject anymore. That’s why we always have to change them.

CRH So maybe that’s the way to end this interview, to pose that question: What do these things really mean?

TA I can only go back to something that guides me in my work, and maybe in my life, a line in a book on James Baldwin called, Artist on Fire, where James Baldwin says that what he’s tried to do is pull the hanky completely out of his pocket. He’s tried to live, where he’s lived all of his life, as fully as he could. And my desire as an artist is to do the same. Not only with my living, but also with my work, to pull out as much of myself as I can possibly pull. That’s the most important thing an art-maker can do: pull themselves out, discover themselves, become who they already really are.

Curlee Raven Holton teaches studio art and African-American art history at Lafayette College. His writings on Afrocentrism in Contemporary Art are widely published. He is also a painter and printmaker.